US President Donald Trump’s tariff policy is certain to strain America’s relations with its partners, potentially pushing them closer towards China, observers say.

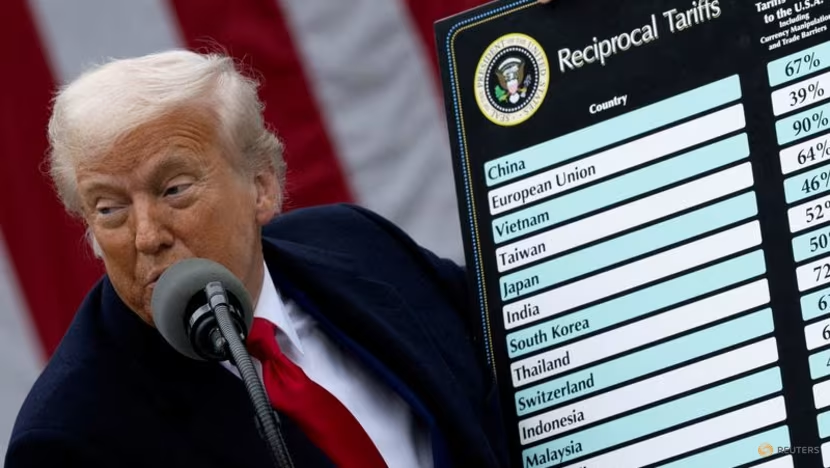

In April, United States President Donald Trump promised to work on 90 deals in 90 days before enforcing his sweeping reciprocal tariffs.

Three months later, only two agreements have been reached.

The first is a limited deal with Britain to keep a 10 per cent rate on most goods, with preferential treatment for some sectors. The other is with Vietnam, with import tariffs slashed to 20 per cent from the previously proposed 46 per cent.

Trump has since postponed his tariff deadline from this month to Aug 1, but doubled down by sending letters to more than a dozen nations threatening them with elevated duties if they fail to strike a deal.

As trading partners scramble to negotiate, analysts said it is difficult for allies to take a hard stance when they have to balance economic, diplomatic and defence ties.

“Probably the best way to negotiate the tariffs is to be very tough, as the Chinese were,” said James Crabtree, a distinguished visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

“(Beijing) did what US allies couldn’t do – which was using rare earth (minerals) as a point of leverage.”

Washington and Beijing agreed in May to temporarily lower steep tit-for-tat tariffs on each other’s goods, and last month confirmed a trade framework had been reached.

But for allies dependent on the US, economic interests and national security concerns are often at odds, Crabtree said.

“If you push back hard on the economic side, the big risk is that Trump then (refuses) to sell you any more F-35s,” he said, referring to the stealth fighter aircraft that the US manufactures and sells to its closest allies.

“So, getting this balance right is extremely difficult.”

DIPLOMATIC TIES UNDER STRESS

Japan and South Korea, the US’ key allies in Asia, are facing levies of 25 per cent. Negotiations initially showed promise but seem to have moved further away from an outcome.

Trump last week called Tokyo “spoiled” for its reluctance to import US rice.

“This is perceived to be a humiliation for Japan. It tried to do a comprehensive deal, and failed,” Crabtree said.

“It doesn’t look good if you’re a US ally and you’re being treated like this. In Tokyo and Seoul, there will be a lot of bad feelings about the way that the US is treating them.”

University of Adelaide (UA) professor Peter Draper said the deadline extension is unlikely to deliver more trade agreements, at least to the tune of Trump’s expectations.

“The US is not exactly in negotiations mode. It’s in demand-making mode, for the most part just expecting countries to concede and concede,” he told CNA’s Asia First programme on Thursday (Jul 10).

WHAT’S WITH TRUMP’S TARIFFS?

Trump has insisted the reciprocal tariffs will narrow the trade imbalance between the US and its trade partners. The policy will also incentivise businesses – both American and foreign – to set up shop in the US, creating jobs.

But analysts pointed to a bigger elephant in the room: China.

The US’ largest bilateral trade imbalance by far is with China – US$295 billion in goods deficit last year. Washington also accuses Beijing of stealing American intellectual property, as well as engaging in unfair trade practices.

“(Beijing channels) funds to companies to give them an unfair advantage … and use the power of the government to keep foreign competition out. That’s why the US has responded with all of these tariffs on China,” said Steven Okun, CEO of advisory firm APAC Advisors.

Chinese exporters have tried to dodge the tariffs – which Trump launched in 2018 during his first term as president – by rerouting manufacturing or shipping through other countries, many in Southeast Asia.

Members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are among the hardest hit by tariffs as goods “skirt blocks put in place through tariffs and other investment restrictions” through these countries, Okun said.

“ASEAN is China’s B team,” he added.

The bloc’s members Laos and Myanmar could be slapped with 40 per cent tariffs come Aug 1, while Cambodia and Thailand are looking at 36 per cent.

Vietnam, even following its deal with the US, needs to crack down on illegal transshipments. Goods deemed to be transhipped will still be subject to a 40 per cent levy.

NOT GOOD FOR AMERICA EITHER

Analysts reiterated that the tariff policy and ongoing deadlock in negotiations are certain to strain America’s relations with its partners, potentially pushing them closer towards China.

“The US is engaging in an act of economic self-harm by cutting itself off from these trading middle powers … trade-intensive Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia, Thailand and Cambodia. This (presents) opportunities for China,” Crabtree told CNA’s East Asia Tonight.

“Trump … focuses almost exclusively on goods trade deficit, completely ignoring the services trade … or (ties with) allies,” said Draper, pointing to traditionally close partners of the US such as members of the European Union.

“The (Europeans) don’t get any favourable treatment. In fact, in some ways, they are treated even worse than some of US’ longstanding geopolitical foes like Russia,” added the executive director of UA’s Institute for International Trade.

The Trump administration has justified a lack of tariffs on Russia due to sanctions imposed over Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine.

Crabtree said that Trump likely believes his tariff policies are successful as, in the short term, there would be higher purchases of US goods and lower trade barriers for American firms.

“But in the long run, it’s very damaging to the US and its reputation as a reliable and economic partner of choice,” he said.

“(We) end up with regions which the US is less connected to, (including) the emerging economic powerhouses of Asia. Trade and globalisation (will also be) limited. All of that is bad for the US.”

Source: CNA/dn(lt)